One of the most fun parts of being a night photographer is experimenting with light during long exposures. Some people do it for practical reasons, like adding light where it's dark. Some use it to add creative or artistic flair to an image. Whatever your purpose, I am going to show you how to build a kit for both painting and writing with light.

I want to first establish some definitions:

Light painting: adding light to something within your frame—e.g. shining lights on the grass, trees, people, rocks, etc. This light bounces off those objects, defines them, and comes back to the lens.

Light writing: turning your light source toward the lens—in effect, you are "writing" with the light, capturing its vector, or path, through space in single or multiple exposures.

For the record, my definitions are not universally adopted or applied. Many people refer to "writing" as "painting." It's neither right or wrong, as long as we all get along. ;-) But for the purpose of this article, let's agree on the above.

I use both methods to make long exposures at night. Both practices have a practical purpose and identifiable effects.

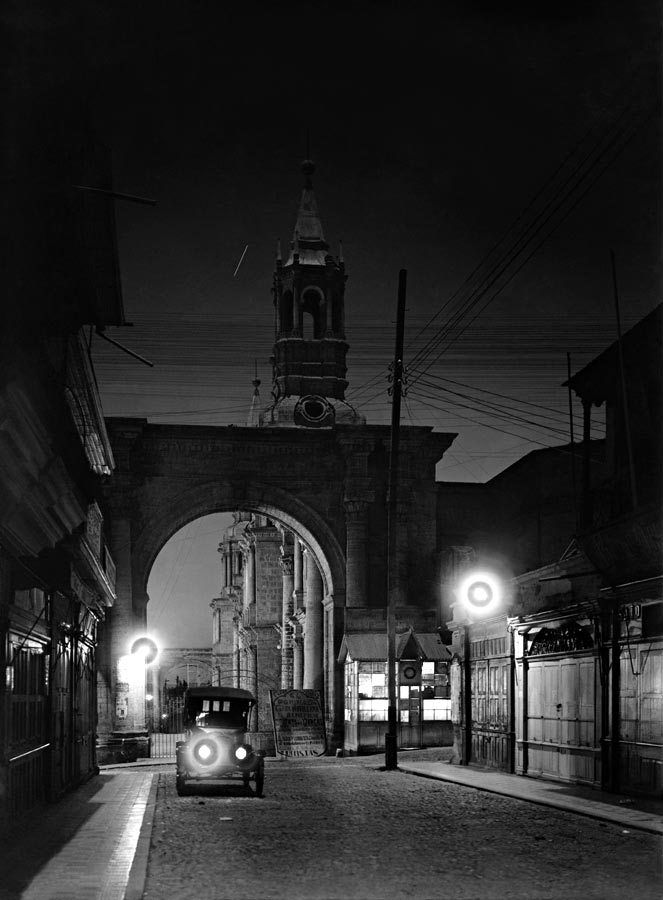

Identifying Light Painting versus Light Writing

In Figure 1, you'll note that a proper exposure that does not blow out highlight details in the sky leaves the foreground lacking sufficient detail. Light painting to the rescue in Figure 2. Both images are from the backcountry of Valley of Fire State Park in Nevada.

In Figure 3, you'll see a starlit scene with a Pixelstick used to light-write around a tree in the foreground.

Figure 3. The Windows at Arches National Park just before moonrise, with light writing done with a Pixelstick. 68 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 6400 with a Nikon D750 and Nikkor 16mm f/2.8 fisheye lens.

And just for fun, Figure 4 is an example where I played catch with my friend using a Frisbee with a blue LED in it.

Figure 4. Three 2-minute exposures stacked. You try vigorously throwing a Frisbee for six minutes in Denver. I'm still catching my breath.

Figure 5. From left to right: Coast HP14 (629 lumens, 813-foot beam), Coast HP7R (300 lumens, 754-foot beam), Coast HP5R (185 lumens, 600-foot beam) and Coast A8R (low-power, 62-foot inspection beam).

Light Painting Starter Kit

If you're just starting out with light painting, let me be the first to say, "Welcome!" You're going to have a blast. You'll want just a few items to get you on your way to opening up more creative roads than you'll know what to do with. Here's what you need to get started:

1. One high-power flashlight with a tight or focusing beam for illuminating objects in the distance. I suggest 300 lumens or more. I use the Coast HP7R (Figure 5) most often.

2. One penlight for writing stuff in the air and for observing things on your camera. (I just fell in love with the Coast A8R, seen in Figure 5.)

3. One pack of Rosco sample gels to warm or cool your light temperature or to make funky colors.

4. Some gaffer tape. Because, you know, gaff solves nearly anything for a night.

Figure 6. Coast FL75R dual-beam focusing rechargeable headlamp.

Light Painting Advanced Kit

Wanna level up and get serious? Roll up your sleeves and bring a bigger bag. Include all of the above, plus:

1. One headlamp (Figure 6) for hands-free safety while trekking around in the dark, and/or for hands-free gear operation. Just be careful not to ruin anyone else's shots when wearing it. Or to blind them by looking at them when it's on.

2. One massively high-power flashlight for light-painting distant objects. I carry the Coast HP14 for this (Figure 5).

3. One kinda-low-light flashlight for delicate work—around 100 to 200 lumens at most. See the Coast HP5R (Figure 5).

4. One good incandescent flashlight for painting with a warmer color temperature than sans-filter LEDs. It might stay in your bag a lot, but sometimes it's just the right solution.

5. One roll of Cinefoil. Cut some, fold it up and put it in the bottom of your bag. Use it to make your own snoots anytime.

LIGHT WRITING KIT

Mechanisms for light writing are a bit different, and come in all shapes, sizes and builds for varied situations. You can learn how to use these tools for their intended purposes, and then use them for anything else you can think of too. Creativity is the key.

Here are some good options to get ya going.

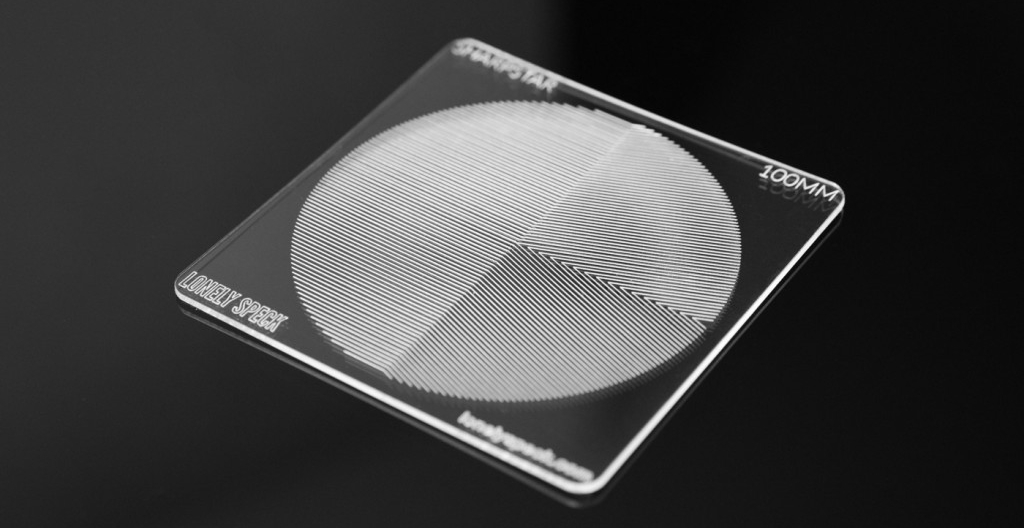

1. One Pixlelstick (I was backer No. 243 on Kickstarter!), or the similar Lumibrush, or any of the fabulous DIY LED arrays if you are technically inclined. (Figure 3.)

2. One Light Painting Brushes Deluxe Starter Kit. This collection of awesome creative tools will keep you playing around in the dark for months. It has everything from the essential Universal Connector (which alone is a great snoot to control light spill), to color cones, a fiber optic wand (I call it the light octopus) and a Jedi-esque light sword.

Figure 7. (No audio.) See the light-beam spread demo from a Coast HP7R, and a quick overview of Light Painting Brushes items mounted on same flashlight, with zoom in/out.

Figure 8. EL Wire.

3. EL Wire. It's inexpensive and makes soft, glowing trails like foxfire. Be careful, though—it's sometimes delicate when transporting and swinging around.

Figure 9. Battery-powered Christmas lights.

4. Battery-powered Christmas lights. With the advent of LEDs, you no longer have to use C or D cells to power them—now it's a pair of AA batteries (light!) and you're good to go. Swing them around to make orbs and light trails. I like to buy them for a dollar or so right after Christmas!

Additional Toys (um ... Tools)

Here is a brief list of other things you may consider using on your path to becoming the night photographer you aspire to be:

- fire (be careful—and do not use inside national parks!)

- fireworks (be even more careful, and be legal!)

- steel wool + whisk + metal cable (I wait for wet, rainy nights to do this or I stand in water—and again, fire, not in national parks!)

- glow sticks

- programmable LED strips

- toys with lights in them

- balloons with glow sticks in them

- LED votive lights

- DIY light painting tools and shapers of all kinds

- professional light painting tools

- lasers

- car headlights and taillights

I use all of these indiscriminately. Why? Well, when you say no to something, your options are limited. So why not try everything and then some?

Now take a deep breath. You can't possibly carry all that with you. Though I have tried...

Below are some more images I've made while experimenting with light writing and painting.