While lunar eclipses aren’t as jaw-droopingly exciting as total solar eclipses, they are still an amazing thing to witness, as well as to capture as photographs. And a lunar eclipse comes with a big benefit: totality lasts much longer than during a solar eclipse, so you have more time to get creative as well as not stress out!

I had last shot a lunar eclipse in 2014, which was a very special time. That blood moon was the second of a tetrad, a series of four consecutive total eclipses that occurred in approximately six-month intervals. The next time that will happen will be in 2032-33. I wonder how we will capture it then! Technology made a major leap from 2014 to 2019, so who knows how it will leap in another 13 years. Maybe we will be able to witness those lunar eclipses from the moon!

The next lunar eclipse will occur in two years, on May 26, 2021. In the meantime, we wanted to share a few tips that we learned this year to help you better prepare not only for the next eclipse but for shooting the moon in general.

And by “we,” I mean a few more people than usual. First I’ll talk about my experience shooting the eclipse this week, and then Matt will add some thoughts from his experience. Finally, we have invited six of our National Parks at Night workshop alums to share their images and lessons learned.

Onward … to the moon and beyond …

11 Tips and Tricks from the 2019 Lunar Eclipse

1. Do your research.

Understand the location you will be in to capture the moon. Will you be in an urban or rural environment? How can this location help tell your story? I saw lots of wonderful lunar eclipse phases placed over breathtaking landscapes, buildings, etc. You could do the same in an urban location.

For this year’s lunar eclipse, I was in Atlanta, a city I wasn’t that familiar with and had little time to scout. I was inspired by the skyline I saw while driving into the city, and I noted that there were plenty of overpasses that could provide a good vantage point.

2. Ascertain the elevation of the eclipse.

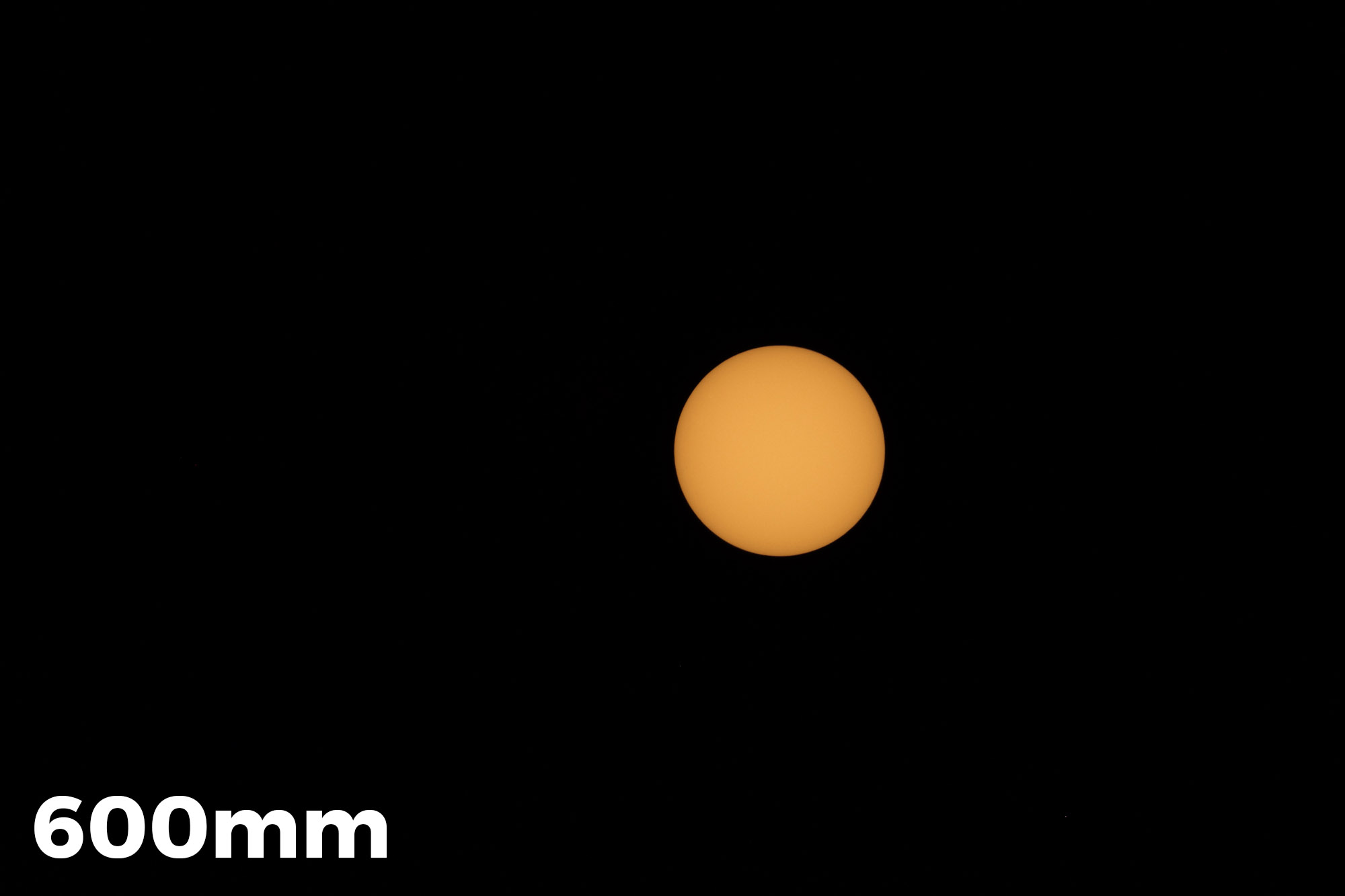

The 2019 super blood wolf moon (aka the lunar eclipse) over Atlanta. Foreground: 35mm lens, 25 seconds, f/16, ISO 200; background (moon): 600mm lens, 1/2 second, f/5.6, ISO 3200.

You want to foresee what foreground you can include in a single shot. I was really taken aback by how high in the sky this lunar eclipse was. It was very difficult to introduce foreground into the scene unless you were really far away or made a composite.

In hindsight, I could have gotten under the Skyview Atlanta Ferris Wheel downtown and probably made a pretty cool shot—but my last photo of a lunar eclipse (in 2014) included a Ferris wheel and I didn’t want to be known as that guy! This did make me realize that figuring out the problem—i.e., the height of the moon in the sky—can lead to unusual solutions like actually getting under your foreground to get the shot!

3. Go with two rigs.

The lunar eclipse lasts approximately 4 to 5 hours. Give yourself more options to create! It could be wide and telephoto rigs, or short-exposure and long-exposure setups.

4. Be ready for that close-up!

That big ol’ blood moon, 2019.

This is advice for shooting the moon any time of the year: Use a telephoto lens. The more you can fill your frame, the better. Higher-resolution cameras will also allow us to crop into the image more with minimal loss in detail.

This year I used a 100-400mm lens, which when zoomed in all the way was the equivalent of a 600mm with my APS-C sensor. I still cropped into the moon in post and would have preferred an effective focal length of 800mm to 1000mm in the field. While those lenses might seem expensive and out of reach, consider using crop-sensor cameras with 200-500mm or 150-600mm lenses. Also, you could adapt a telescope to fit your camera and can easily get to 1000mm.

When using a super-telephoto lens and aiming it high in the sky, watch out for lens creep, which is when your lens zooms slightly during the exposure. I once found this to be the culprit of a soft image, when my Fujifilm 100-400mm lens wouldn’t lock down at one focal length. Eventually it stayed put, but the problem was a bit frustrating and ruined several of my shots. Always zoom in and review your images.

5. Don’t forget your wide lens.

Telephoto lenses get most of the love during the eclipses, but wide-angle lenses can offer better storytelling. They can tell something else about where the image was shot—just think about what other elements of the scene you want to combine with the moon. Two rigs gives you that option.

6. Allow plenty of time to play.

We mentioned that the lunar eclipse lasts a while. The totality, or umbra period, can last 1 to 2 hours. That’s a lot of blood moon! While the umbra phase can be the most exciting, start clicking as soon as the penumbra starts, when the moon remains white but starts to show all its phases as Earth casts its shadow.

7. Try a moon trail!

High Roller & Lunar Moon Trail, 2014. 55mm focal length, 15 minutes f/8, ISO 400.

With so much time, why not set up one rig dedicated to shooting the entire eclipse and then stack it together for a very unique moon trail? The beam will be wide and bright during the penumbra period but get skinnier and a little dimmer during the umbra period. I’ve seen only a few images using this technique, and I definitely want to give it a go next time!

Given the length of this long exposure, you’ll definitely want to make sure you have plenty of power in your camera. I’d at least want to add a second battery and attach a power grip—but for even more power and reliability I’d hook up the camera to a Tether Tools Case Relay or ONsite power solution.

8. Do a time lapse or capture some video.

I’m a still photographer, but moving images can help tell a story in more detail. This could be especially helpful if you are battling clouds or weather. Dedicate that second rig to video and keep that powered up with the Tether Tools solutions listed above.

9. Zoom while exposing.

I slapped my hand against my head when I saw these images pop up on social media. I love this technique for neon signs and buildings but it didn’t cross my mind with the moon! Especially during the dimmer umbra phase, you can get exposures of 3 to 8 seconds. Use a telephoto lens zoomed all the way in, then midway into the exposure zoom to the widest end and leave it there. Two moons for the price of one!

10. Include the moon with other night elements.

Match up that moon with car trails or other bright things that move. We often default to the telephoto close-up of the moon, but how else can we tell the night story? Emphasize movement in your image! In my image from Atlanta, I really wanted car trails and the lunar eclipse—I wanted those leading lines taking us to the moon! Perhaps you could shoot the moon next to moving water, or add star trails surrounding the moon.

11. Composite away!

Full moon and eclipse photography are techniques that totally lend themselves to creative and fantastic composites. Show us all the phases of the eclipse in an interesting pattern. Place the moon anywhere in the world! Compositing images—taking elements from multiple shots and combining them—can totally unleash a new fantasy location.

My advice on compositing is to have a clear vision and stay true to it. Larger-than-life moons make a viewer realize the moon “doesn’t belong” in the scene, however if the rest of the image is pure fantasy then it is totally acceptable. In my image from this week, the moon is bigger than it normally would have been but still has a somewhat realistic feel.

Photographer vs. Freezing Temps

by Matt Hill

The night of the lunar eclipse, it was frigid in Catskill, New York. I mean cold. 3 degrees F cold. (Interpret the “F” how you want.)

Also, I was feeling really under the weather. But I really wanted to grab some frames of the eclipse, despite all these roadblocks.

So I popped open PhotoPills and saw that the super blood wolf moon would be arcing right between the houses by my studio. I decided to shoot it from the tiny deck outside the studio door.

The Weather Underground app (left) and PhotoPills’ eclipse and Night AR features provided all the info needed about where and when to shoot the eclipse in Catskill, New York.

For about 2.5 hours, I popped in and out, trying to avoid frostbite, and I worked through an image sequence that got me fully into totality.

And then, for kicks, I ran through optimizing exposure length versus ISO during totality. I mean, it was an hour long, right? The worst thing I could get was frostbite.

I settled on shooting at 1/2 second and ISO 100. I liked it better than any of the images I shot at higher ISOs. I made this sequence of images from the set:

Nikon Z 6, Nikon 300mm f/2.8 lens. 1/125, f/14, ISO 100 (full moon); 1/2 second, f/4.5, ISO 100 (totality).

Then I thought it would be great to run one more experiment to see at what shutter speed a 300mm lens would make the moon too blurry to be seen clearly. It’s easy to do with a full moon—but I wanted to have this to show people what it looks like during an eclipse:

Honestly, I thought the 1/2 second exposure was the sharpest that was acceptable to me. Either way, note that the chart above is for a 300mm lens. Results will be even more restrictive with a longer lens, such as a 600mm. It’s important to bracket and test in the field.

Exhausted and tired, I put my gear inside and rolled into bed around 1 a.m.—after downloading and inspecting my images, naturally. ;-)

Eclipse Stories from NPAN Alums

For several days this week we saw some of our workshop alumni post incredible images on social media. We asked a few if they’d share their stories and lessons learned, and we were thrilled that they are happy to do so.

by Gary Domrow

© 2019 Gary Domrow, instagram.com/gsdpic. Canon 5D Mark IV, Canon 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6 lens with teleconverters. 1/2 second, f/8, ISO 1600.

I set up the tripod up in my driveway here in Austin, Texas. I had hoped to do a sequence but the first part of the eclipse was obscured by clouds, so I took pictures for just about 15 minutes on either side of the beginning of totality. I shot them using the Canon 100-400mm, some with the Sigma 2X teleconverter and some with the Canon 1.4X, set up on a Really Right Stuff tripod and ball head. I used the “live view and zoom in” method to focus, and actually remembered to try a few different settings for ISO, shutter speed and aperture.

Despite using that lens and teleconverter combination, I must not have been zoomed in quite all the way because the focal length is 525mm according to the EXIF data. So I cropped the final image. What you see is maybe 30 or 40 percent of the original frame. Finally, I did some minor tweaking in post with Lightroom—Exposure, Contrast, Noise, Clarity.

I guess I can’t say I learned anything new. I just practiced and reinforced the techniques that I have, which is also a good thing.

Well, I did learn later that some people are really lucky—did you see this article about the meteor hitting the moon during the eclipse? I guess as long as you are out shooting the night sky, there’s always a chance you’ll catch something unique or interesting or unexpected.

by Heather Cunningham Wendelboe

© 2019 Heather Cunningham Wendelboe, bolo-photo.com. Nikon D750, 20mm f/1.8 lens.

I’ll pretty much always have a story, because every time I go out on one of my “automotive astroscape shoots,” I set myself up for a major mistake—since I always want to try something I don’t know how to do! So here’s the whole story of my disaster.

I had planned for one my usual automotive astroscape shoots. My intention for my final image is always to share a vision as if you had looked out a window and watched the whole experience through the night—to inspire someone to go on a late-night road trip out there in the middle of nowhere. A secondary intention is to showcase my passion for driving these cars the way they were meant to be driven and not just hoarding them in a garage.

This was my first attempt at a lunar eclipse. I wasn’t thinking about what would be different than other night photos I’ve done, so I composed like I normally would. The focus and exposures actually turned out pretty good, considering the haze in the sky and the lens fogging up, not to mention the microscopic size of the moon with a 20mm lens! The main problem was that at the time I started shooting the moon, it was in the middle of my frame, and there was not enough room at the top of the frame to fit the entire sequence of exposures as planned. So, right about the time of maximum totality, the moon just dropped off the edge of the composition!

I wish I had set up the camera to shoot the entire sequence of the eclipse, and then I could have done a second setup for the composition and foreground exposure, since the final image would have to be a composite anyway.

When it came to editing, I cropped out about two-thirds of my frame to make it a vertical, which helped get rid of a lot of the vertical line distortion and placed the moons in a better position from side to side. But with the vertical orientation, looking from top to bottom, I ended up with literally the middle third of my frame being blank sky. I posted that version to the National Parks at Night Alumni Facebook group. After talking with several people in the comments about all our lunar eclipse photos, I decided to try a re-edit: I moved the moon sequence lower to fill the blank sky, then I cropped it back to horizontal.

Moving the moons to an inaccurate position in the sky bothers me, because no one who could have been there watching that scene would have seen it this way. But the resulting composition is acceptable.

Lesson learned: You can’t recover what you didn’t shoot. And if you mess up what you did shoot, you owe it to yourself to salvage it, because your failed attempt required the same effort that a successful one would have. It wasn’t your work, only your decisions, that made the difference.

by Randy Christ

© 2019 Randy Christ, MovingImagesPhotography.com. Canon 5D Mark IV, Canon 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6 with 1.4X teleconverter, on an iOptron SkyGuider Pro EQ Camera Mount. 20 seconds, f/8, ISO 100.

The photograph is a single image—no HDR, no compositing, no Photoshop. All the editing, cropping, etc. was done with Lightroom.

Image stabilization was turned off, and focus was set to manual. The camera was mounted on an iOptron SkyGuider Pro EQ mount, which was configured to track the moon precisely. The 20-second exposure time was chosen to hold in check the star trails that would occur due to the moon and stars moving at different rates in different directions. Also, this shutter speed allowed for the settings of ISO 100 and f/8, which are the sweet spots of this camera and lens.

This was my first attempt at shooting with an EQ mount, and the comedy of errors I made kept rolling all evening. Talk about lessons learned—as well as just some bad luck. But I also had some good luck, and came away with some shots I am pretty happy with.

I decided to process this particular image in the series because it caught the fleeting moment when the moon was just about to leave the umbra shadow of Earth, ending totality. During totality, the light that reaches the moon travels through the inner layers of Earth’s atmosphere, which passes along the longer-wavelength orange and red light. This is why the moon turns orange during totality. In the moments just prior to reaching the end of totality, some light reaches the moon after having passed through Earth’s ozone layer, which passes along blue, shorter-wavelength light. This results in a small strip of purple trim on the leading edge of the moon. It is a unique and splendid moment that occurs for only a brief moment in time.

Note: If you’d like to read more about how Randy created this image, see his blog post “Total Lunacy—Photographing the Total Lunar Eclipse.”

by Martha Hale

© 2019 Martha Hale, instagram.com/marthahale. Canon 5D Mark IV, Canon 70-200mm f/2.8 lens.

I was fortunate enough to shoot the solar eclipse of 2017 with National Parks at Night, so I knew I wanted to give this lunar shot a foreground element. Using PhotoPills, I scouted numerous skyline and landscape possibilities around town, only to realize this event was going to be happening straight up in the sky far away from the horizon. Change of plans. I scouted taller locations such as the statue of Vulcan in Birmingham, but newly installed multicolor LED lighting was going to be a challenge. I pondered Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark, but without NPAN, would they let me in that late again and turn off all the lights? Slim chance.

At the entrance to my neighborhood is a rather large replica of the Statue of Liberty. I couldn’t resist. I ended up liking a composition from directly beneath the statue with my lens aimed straight up, shooting with a Canon 5D Mark IV and a 70-200mm lens. I bounced all night between that and a Fuji X-T3 setup with a 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6 lens plus 2X extender. I was struggling with the loss of stops at f/9 with the Fuji, and with chasing the moon to keep it in the frame (should have used my star tracker from the previous eclipse), and with having to bump up the ISO so much once we were in totality.

I was getting frustrated, so when my husband came to check on me, I was ready to pack it up. But first I handed him a flashlight and asked him to point it at the face of the statue. I went back to my Canon and decided to do one final composition with my focal point on the statue, and just to be sure, took the time to do one more shot focusing specifically on the moon. I’m so glad I took that extra step, because when I got back to the full screen of my computer, the moon was slightly out of focus in all the earlier shots! I stacked the two shots in Photoshop for the win!

by Susan Wales

© 2019 Susan Wales, susanwales.ca. Nikon D810, Sigma 150-600mm f/5-6.3 lens.

I did not do a time lapse, but rather only took individual frames and put them together in Photoshop later. It would have been hard to do a time lapse because the settings changed a lot from the beginning to the end of the eclipse.

I did not realize that the color of the moon would change so dramatically from white at the start until the blood moon color developed with the full eclipse. That was fascinating to watch.

I pre-focused to infinity, locked my focus down and then shot in manual mode. I started to photograph at 8:50 p.m. (in British Columbia) and finished at 10:09 p.m. when the clouds moved in. I started with an exposure of 1/6 second, f/5.6, ISO 64 and finished at the height of the eclipse at 1.3 seconds, f/5.6, ISO 2000. I adjusted my camera settings manually as the light changed on the moon.

by Steve Winker

© 2019 Steve Winker, whereswinker.com. Canon 6D, Tamron 150-600mm f/5-6.3 lens.

I shot the eclipse from the RV Park I’m staying at in Tucson, Arizona. Unfortunately, my site is right next to a 40-foot wall separating the RV park from Interstate 10. So there wasn’t any decent foreground. Plus, there’s a very tall bank of lights right there.

The main thing I learned was that I shouldn’t have set up so close to a very strong light source high in the air. At totality, it was almost impossible to see the moon thru the haze created by the light. The strong haze also caused my photos of the moon at totality to be a little hazy.

I really didn’t learn too much else this time. But I had shot a lunar eclipse in 2014 and I applied what I had learned from that shoot to this one. Based on that shoot and the fact that I didn’t have a foreground to use, I made the decision to zoom in and make a composite using several stages of the eclipse.

I did no cropping. I just took the five frames into Photoshop as layers, masked out the sky in each layer, and then moved the five layers so that the moons lined up.

Wrapping Up

Thank you to those six fantastic alums for sharing their images and their stories! We’re continually inspired by the photography we see coming from the fine folks we get to work with throughout the year.

So, who’s next? How about you? We’d love to see your photos of this week’s lunar eclipse, and to hear the stories behind them and the lessons you may have learned. Please feel free to share them in the comments section below or on our Facebook page.