At first glance, the National Parks at Night mission might appear to be solely about venturing into parks in the dark to teach night photography. But our broader mission is much … well, broader. It’s about pushing the envelope for the entire world of night photography.

To that end, we’ve been quietly working hard for the past 14 months to develop our first tangible product—a set of tools that will at once help established night photographers expand their creative potential and give new night photographers an easier way into the niche.

And finally, we are very proud and excited to announce the National Parks at Night “Day For Night Filters.”

This is a toolkit of seven classes of filters—available individually, in sets or in one comprehensive package—designed to allow certain types of night photography to be executed even when conditions aren’t right for traditional approaches to shooting in the dark.

The idea behind the filters is born from the old-time filming technique of “day for night”—essentially, using daytime light conditions to produce a nighttime look. But while the film crews of yesteryear generally accomplished this effect simply by underexposing, this toolkit goes a step further.

How The Filters Work

All our filters feature a neutral density (ND) base layer, which is then etched to produce different common astro-landscape looks when photographing a daylight scene. The etched portions allow daylight in while the ND portions keep other areas dark. The combination allows for a wide range of effects, from star points to star trails to the Milky Way and even auroras! Plus much, much more.

The ND portions, however, are not completely neutral—they have a cool-toned coating (mired-blue, for the tech-minded reader) that produces a truer “nighttime” look. Conversely, the etched portions of the filters have a mix of warming tones. This DualTemp (patent pending) combination of these two color-correcting filter technologies produces images that look exactly as if they were photographed at night.

The Toolkit

Our initial rollout is a selection of filters crafted to reproduce the most popular night photography scenarios, as detailed below.

(Unless otherwise noted, all filters are available in rectangular format in sizes 85mm, 100mm and 165mm.)

Star Points Filter

The most basic of our Day For Night Filters is the “Star Point,” which allows you to photograph “under a night sky” no matter what time of day you’re shooting. The neutral density overlay is pocked with tiny pits, each a different size with subtle variations in color temperature, all of which combine to create a highly realistic starry sky effect when shot with daylight color temperatures.

The Star Points kit includes three filters with different densities of stars, for maximum creative leeway.

Star Trails Filter

Sometimes stationary stars aren’t enough. Enter our “Star Trails” filter, which allows you to create the illusion of bending time, even with considerably short exposures.

These filters come in different star densities (low-density for fewer star trails, high-density for more), and also come in different trail lengths (4mm, 16mm and 32mm) to mimic various long-exposure times. The entire set will allow for maximum creativity, giving the option to swap in different effects for different scenes.

Star Circles Filter

One of the coolest tricks to round out the night photographer’s repertoire is the ability to produce star circles by pointing north on a clear night and opening the shutter for a good hour or more. But now you can create the same effect pointing in any direction (opening up many more possible compositions), and in much less time!

Our “Star Circles” filters come in two varieties:

Rectangular, which offers a fixed set of star circles that can be positioned to suit the composition by moving the filter up or down in the holder.

Circular, which features a rotating ring that makes the star trails shorter or longer.

Milky Way Filter

Perhaps the most popular night photography achievement of the past decade is the ability to capture the dense cluster of stars of the Milky Way. But even though modern camera technology has put our galaxy in reach of shutterbugs throughout the solar system, photographing it still comes with challenges—namely, having to wait for the right time of year to view it, the right time of night for it to appear over the horizon, and its propensity to hardly ever be hovering in a compositionally pleasing place in the scene.

All those issues are solved by using our “Milky Way” filter. It comes in a standard rectangular format, which enables you to place the galactic core anywhere you want in the sky of your composition, and you can then adjust the angle of the core by rotating your filter holder.

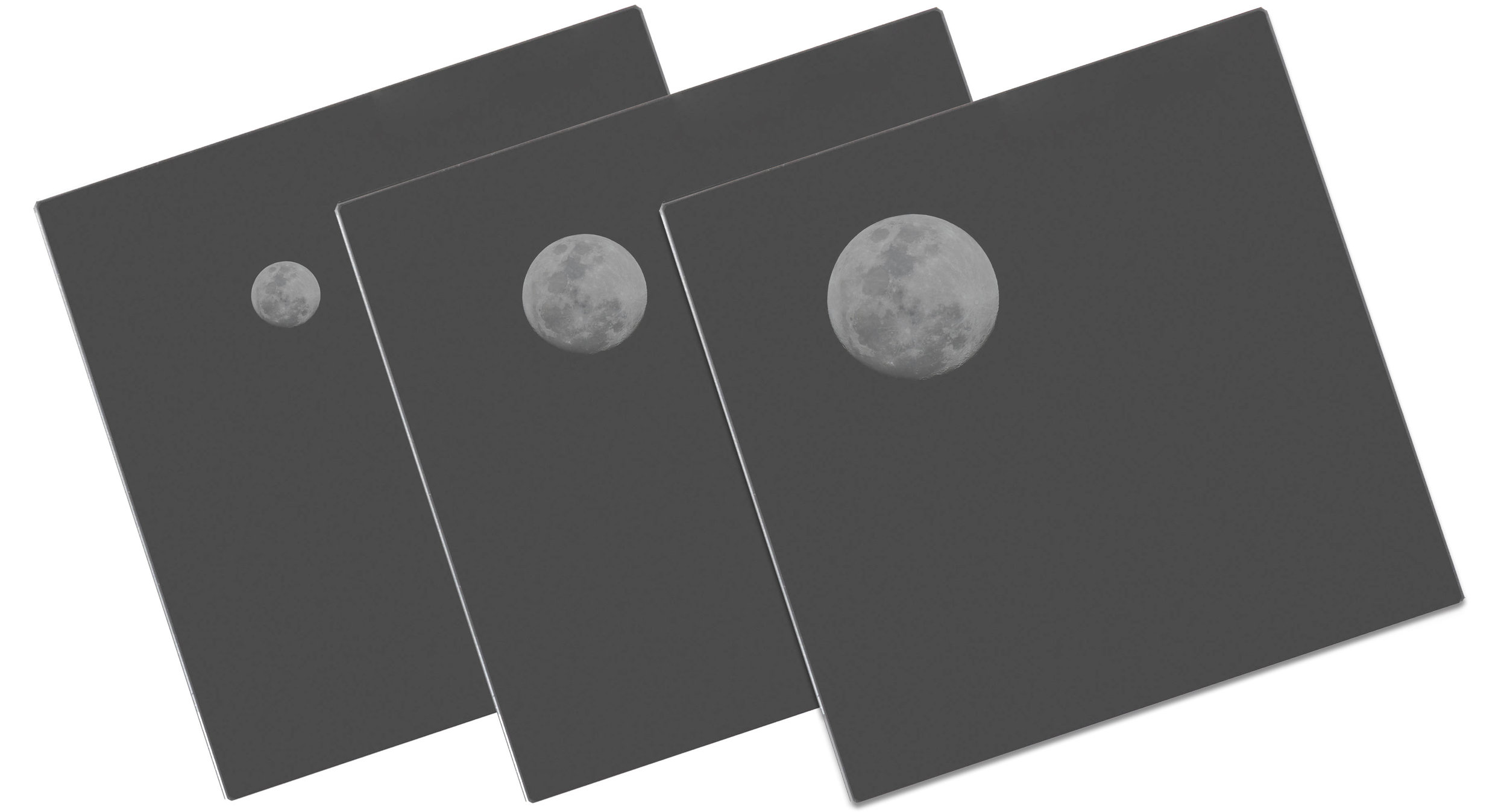

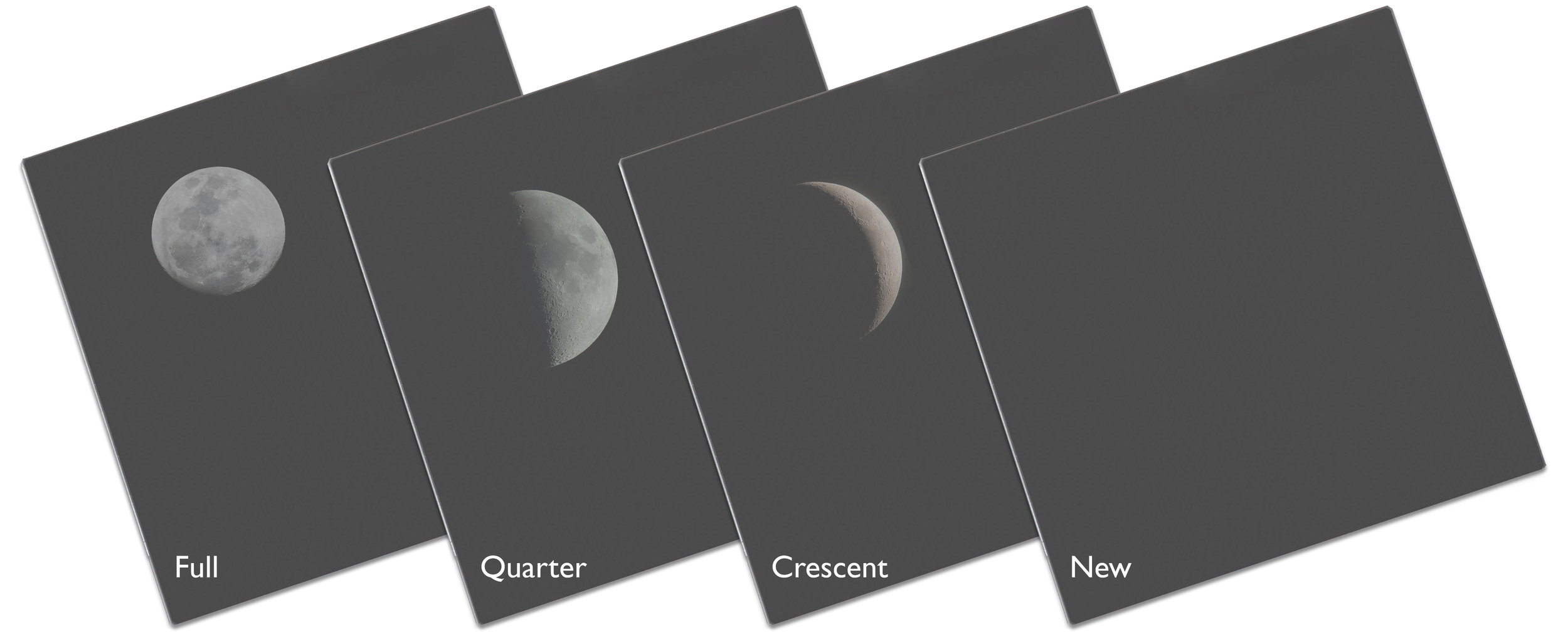

Moon Phases Filter Kit

Normally, if you have a solid idea of how you want the moon to look in a scene, you need to do a lot of planning to make it happen. Earth’s only satellite floats all over the night sky, and its particular phases appear only once per month.

All these challenges dissipate once you begin using our “Moon” filters. A set of 10 filters allows you to add the moon to any scene, in any way you want. The entire “Moon Phases” kit features the moon in three different sizes (grande, venti and trenta) and four different phases (full, quarter, crescent and new).

Moon filters can be used alone for a clean-sky effect, or stacked with Star Point filters for a combined, starry sky effect.

Aurora Filter

We almost didn’t manufacture this filter because of the technical complications first in manipulating the necessary technology, and then in actually constructing the glass. But to be honest, it’s the filter we’re most excited about: the “Aurora.”

Until now, photographing auroras has been the playground only of those willing to travel to far-flung polar regions, such as the popular photography destinations of Iceland, Norway and Red Dog Mine, Alaska. But if you want to shoot the northern lights from your own back yard, then this filter is all you need.

Our Aurora filters come in two varieties:

Rectangular, which offers a fixed aurora that can be positioned to suit the composition by moving the filter up or down in the holder.

Circular, which features a rotating ring that changes the shape of the aurora!

(If you live in the Southern Hemisphere, please be sure to order the “Southern Lights” filter for the most accurate results.)

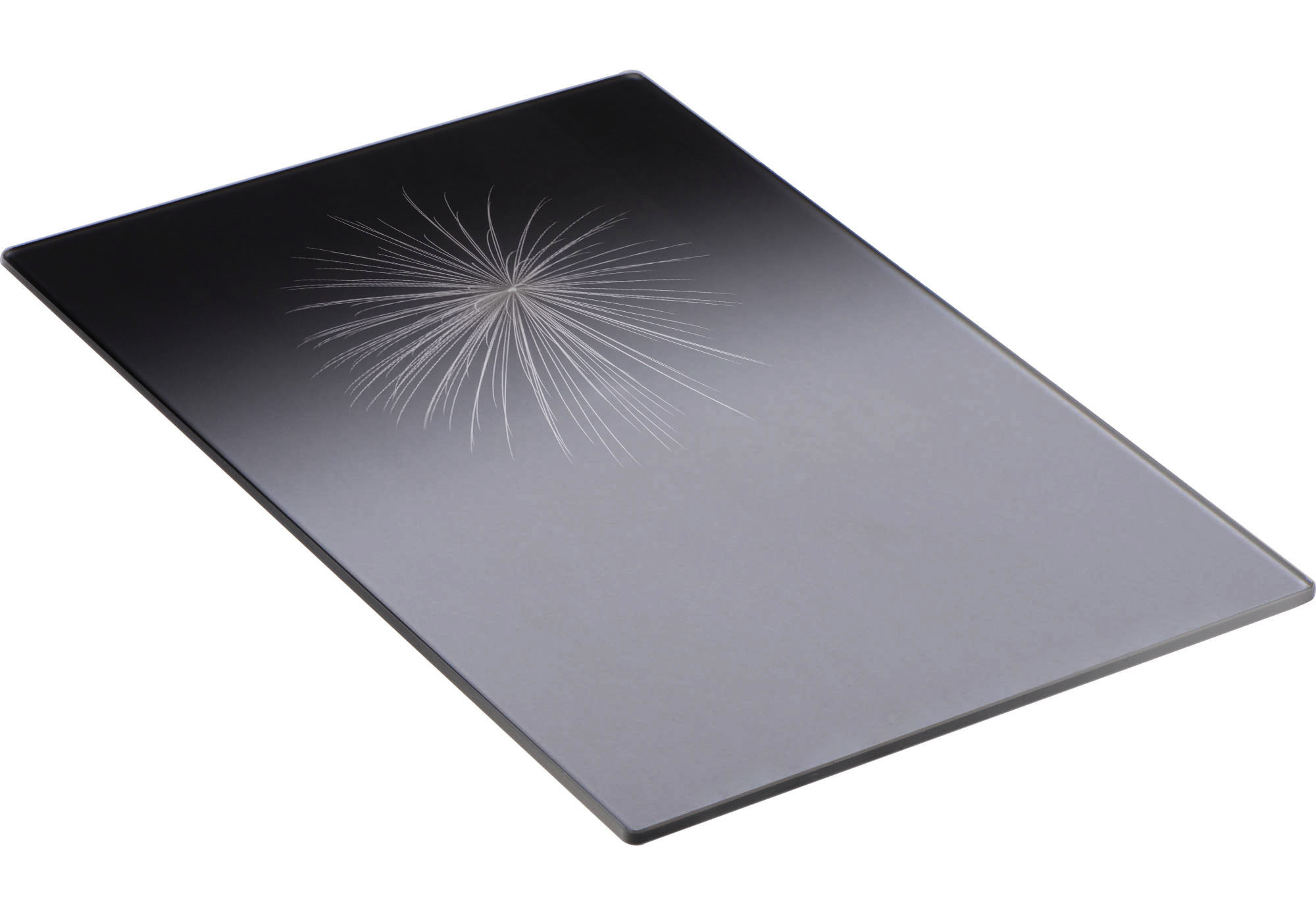

BONUS! — The Keimig Firework Filter

For a limited time only, free with any purchase of three or more filters is an out-of-the box idea from National Parks at Night partner and instructor Lance Keimig, whose motto is, “There’s no night landscape that doesn’t look better with fireworks!”

The “Keimig Firework Filter” is rectangular, making it positionable so that you can place the firework where it serves the composition best. Now any day (or night) can be the 4th of July or New Year’s.

(Coming this December, be sure to look out for our “Keimig Kristmas Lights” filter set, which will accomplish similar results. Decorate the rim of the Grand Canyon!)

Filters That Solve Problems

We’re confident that our Day For Night filters will solve many of the entry barriers to nocturnal photography, and will also help ease the burdens of experienced night photographers. Quite simply, night photography is hard, and these filters make it easier.

No more need to wait for Milky Way season.

No more need to travel to aurora “destinations.”

No more in-the-dark focusing hassles.

No more looking for something to do during crazy-long exposures.

Get to sleep at a reasonable hour.

How to Purchase

All of our Day for Night filters are being carried exclusively by B&H Photo in New York City, as well as the camera department of the General Store in Bodie, California, and are available for purchase immediately. Please click the button below to order.

Get Creative!

The only thing that excites us more than developing and releasing these filters is that now we get to see what you do with them. We encourage you to get out into the field, use these great new night photography tools, and share your images in the comments section.

Seize the night! (Or day!)