I learned early on in my career that revisiting sites and images over time can lead to a deeper understanding of the landscape, as well as to better and less obvious photographs. In a way, this is like going back to reprocess an older image after gaining more knowledge of post-processing software, except you’re remaking the image in person—bringing additional personal experience, acquired skill and a more mature mindset to the scene.

Of course, multiple factors can change in addition to the photographer’s vision or perception, most of which have more to do with the location than the photographer. Places are different across the seasons, in different weather and during different phases of the moon.

If you first visit a place in winter, perhaps coming back in early summer to include the Milky Way core in your image would be worthwhile. Other less obvious things can change the nature of a location too––a streetlight that has burned out or been replaced, a car parked in an unfortunate spot, or some other distraction that prevents (or creates) an ideal composition.

In this week’s post, all five of us present examples of photographs that we made on different occasions in the same location.

Panorama Point, Capitol Reef National Park

by Gabe Biderman

I love all the Utah parks, but if you were to ask me which was my favorite … well, I’d have to tip my hat to Capitol Reef National Park.

I was fortunate enough to visit this Gold Tier International Dark Sky Park twice, the first on an epic road trip with Matt, Chris and my brother-in law Sean in 2016. We stopped at the aptly named Panorama Point and fell in love with the S-curve of the road cutting through the spectacular red rock landscape. We talked about driving the car, with headlights on, down the road to emphasize the line, but Matt suggested that we level up by taking advantage of the car’s moonroof—we could hold his Pixelstick out of it and carve a unique band of light around the curves.

It was a true team effort. I ran all three of our camera rigs from the top of Panorama Point, Matt drove the car without the headlights on, and Chris held the Pixelstick straight through the roof. It took a few attempts under the mostly full moon, but this has remained one of my all-time favorite collaborative images.

Take 1, April 2016. Nikon D750 with a Nikon 14-24mm f/2.8 lens at 24mm, light writing with a Pixelstick. 2.5 minutes, f/8, ISO 800.

When Matt and I returned to Capitol Reef to lead a workshop in June 2018, we knew we wanted to share Panorama Point with the group. This time there was no moon and the road that cut through the dark foreground led exactly to the core of the Milky Way. I wasn’t even planning on shooting that night, as I had already taken what I felt was a pretty unique shot of this location—but this was just too good to resist.

The Milky Way was definitely the dramatic feature and could have very well stood on its own with a thin silhouetted foreground. But I wanted to revisit the road. This time I aimed my camera down the opposite end as it curved toward the core. By total coincidence, a car drove down while I was exposing, and this time it ruined the shot—it was way too bright, despite no one holding a Pixelstick!

Because the conditions were so dark, to get the best image quality I shot multiple high ISO frames that I would later blend in Starry Landscape Stacker. To get a clean foreground with good detail, I let in an additional 3 stops of light and shot at a lower ISO (1600). I then blended the sky and foreground. (You can see how I processed the final image in the video that accompanies the blog post linked above.)

Take 2, June 2018. Nikon D5 with an Irix 15mm f/2.4 lens. Sky composed of multiple frames at 25 seconds, f/2.4, ISO 6400; foreground shot at 13 minutes, f/2.5, ISO 1600.

Mesquite Flat Dunes, Death Valley National Park

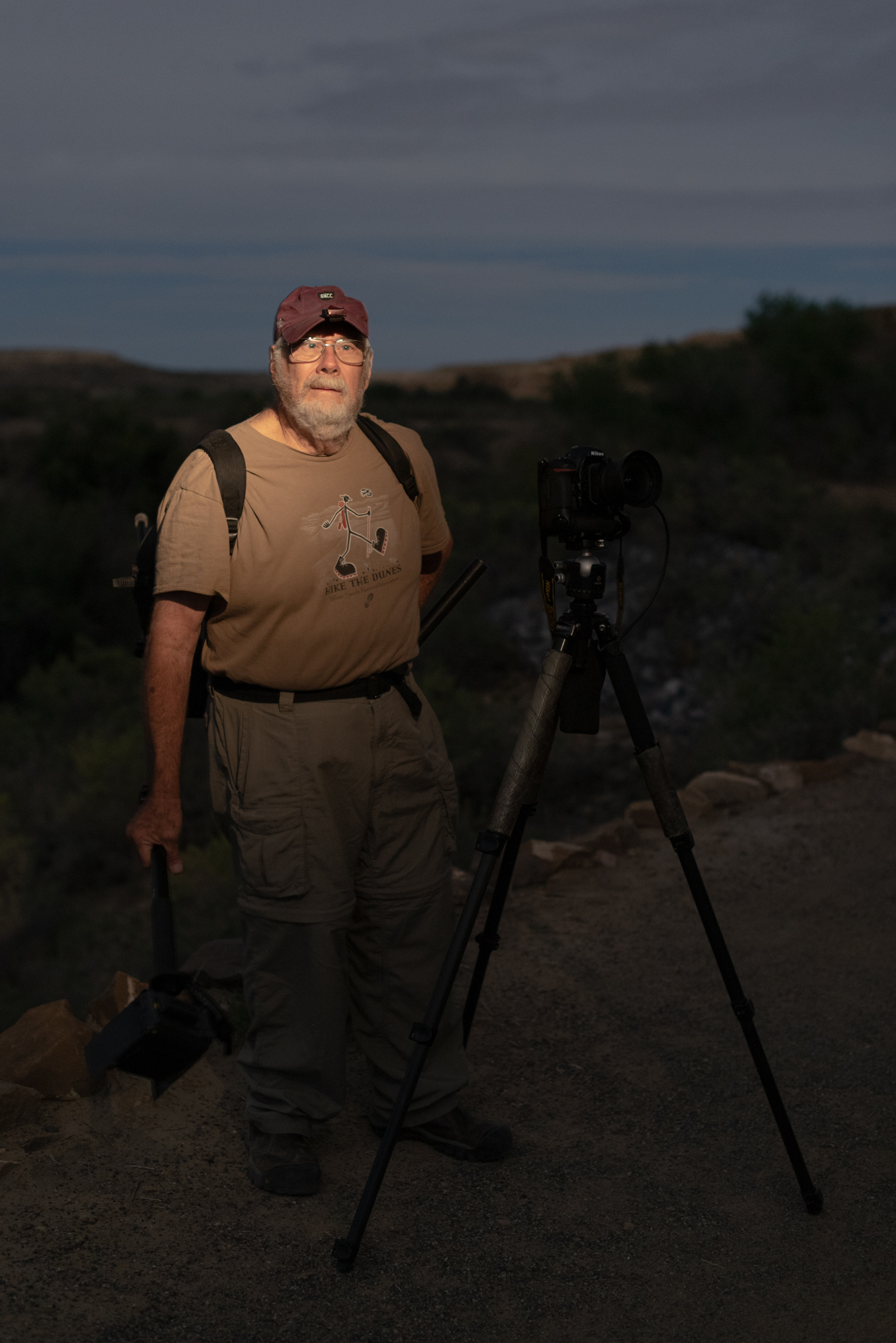

by Chris Nicholson

In 1995 I drove cross-country with a college buddy who was also a photographer. When we got to southern California, we saw that our route took us close to, though not through, Death Valley National Park. For a moment we considered veering toward the park, but instead opted to beeline toward the Pacific. Big mistake. Twenty years later, I finally made my way back and instantly fell in love with this stark and beautiful landscape. I developed an affection for this place that’s so strong, I’ve returned a half-dozen times in the four years since.

One of my favorite locations in the park to photograph is Mesquite Flat Dunes. Everything about this area lends itself well to landscape photography—the strong lines of the dune crests, the patches of playa in the troughs, the ripple patterns in the sand, the way light and shadow interplay, the desert-mountain background on every horizon. Really, you can’t go wrong here.

Well, I suppose you can go wrong, and I have, more than once. One case to prove the point: On my third trip to Death Valley, I wanted to locate and light paint a single shrub among the dunes. I found a good candidate, composed it, lit it … and lit it, and lit it, and lit it … and just wasn’t creating what I wanted. I could see the final result in my head, but couldn’t get the light to match it. Eventually I abandoned the idea and moved on to more successful matters.

Take 1, February 2017. Nikon D3s with a Nikon 28-70mm f/2.8 lens, light painted with a Coast HP7R flashlight. 8 seconds, f/8, ISO 200.

Later that year, on my next trip to the park, I was out in the dunes again, determined to find a way to make my old idea work. I adjusted a few things about my strategy:

I shot later in the evening, toward the end of twilight, when I could have a nice blue sky but also get some stars.

I found a shrub on a more gradual slope, which provided a more uniform background.

That slope was also wide, which provided me an angle from which I could backlight while facing downhill, from well outside the frame—which meant I could light paint from one spot to create nice, hard-edge shadows that didn’t drift off the bottom of the frame.

Not only did this approach work much better than what I’d tried and failed at just 10 months before, but the result ended up being one of my favorite photos of the year. And actually … maybe one of my favorite photos I’ve ever made in Death Valley.

Take 2, November 2017. Nikon D3s with a Nikon 14-24mm f/2.8 lens, light painted with a Coast HP7R flashlight. 20 seconds, f/5.6, ISO 1600.

Marshall Point Lighthouse, Maine

by Lance Keimig

I’ve had the good fortune to teach at Maine Media Workshops for the last several years, and over the course of five or six workshops there, I’ve been able to photograph some of the area’s iconic lighthouses on multiple occasions. Marshall Point Lighthouse is one that never fails to give up a picture that I’m excited to go home with.

A photographer’s vision may change and develop over time, influencing the way that they might respond to a location. But in the three examples shown here, the local conditions at the lighthouse were more significant than anything else.

I first visited this beautiful Maine lighthouse in August 2016 and had the incredible good fortune to experience a little aurora borealis. That led me to photograph the lighthouse from the south, the opposite from where most people usually set up. The exposure was dictated more by the appearance of the aurora than the lighthouse.

Take 1, August 2016. Nikon D750 with a Sigma 24mm f/1.4 lens. 15 seconds, f/4, ISO 1600.

In June 2017, the beacon had been replaced with a much brighter and cooler LED light source, which changed the scene dramatically, even bathing the shoreline across the bay in bright greenish light. My first thought was that the residents of the homes across from the lighthouse must have been dismayed at the change, as their backyards were continuously illuminated by the crazy-bright light. Fortunately I figured out how to compensate for the brightness, by positioning my camera in a way that prevented the lantern from blowing out completely.

By choosing a closer and lower camera position on the northwest side of the lighthouse, as well as blending separate exposures for the lantern and landscape, I was able to keep the bulb out of the frame and therefore control the exposure better than on my first visit. The Milky Way core is in the background, and dictated the overall exposure. In hindsight, I should have used ISO 100 for the lantern exposure to preserve maximum dynamic range.

Figure 2, June 2017. Nikon D750 with a Tamron 15-30mm f/2.8 lens at 20mm. Two exposures of 1/3 and 20 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 1600.

Finally, in both July 2018 and this past May when I went to Marshall Point, lightning was flashing out at sea. The lightning enhanced the images from those nights, and made for a memorable experience.

I used a longer overall exposure and lower ISO to preserve dynamic range and also to allow more time to increase the chances of catching a lightning strike. As it turned out, I captured three of them! I used Lightroom’s Merge to HDR feature to combine the images. The wider angle of view of the 15mm lens allowed me to include the reflection of the lantern in a puddle in the foreground.

Take 3, July 2018. Nikon D750 with a Tamron 15-30 f/2.8 lens at 15mm. Three blended exposures of 8 seconds, 20 seconds and 110 seconds, f/4, ISO 400.

Zion National Park

by Tim Cooper

Zion National Park just may be my favorite park to photograph. Not because it’s more spectacular than any other park, but because it’s simply so rich with photo possibilities. It seems everywhere you look, there is some version of beauty to capture. Day or night, cloudy or sunny, spring or fall, you can always find a photograph here.

My first visit to Zion was in 1994, and since then I’ve led workshops there almost every year. Frequenting the park has given me the opportunity to revisit locations that I love.

I’d had this particular image in my mind for some time but had never been able to pull it off, for one reason or another. Finally during a workshop in 2011 the conditions and timing were just right—or so I thought. A nearly full moon provided the foreground illumination I wanted, and the semi-clear skies allowed for a chance at good star trails. I located the North Star and framed it with the tree and the distant mountain.

Full-moon nights are tricky conditions for capturing star trails. The brightness helps illuminate the foreground, but makes using long exposures difficult. In this example I had to stop down to f/5.6 to achieve a 12-minute shutter speed. While I liked the shot, I never really loved it. The foreground illumination is uneven, the star trails are a bit short (12 minutes isn’t really long enough when pointing north), and I somehow ended up with a gap in the trails.

Take 1, November 2011. Nikon D700 with a Nikon 24mm f/2.8 lens. 12 minutes, f/5.6, ISO 200.

Fortunately, I was able to visit again the following year. Same place, similar moon phase. But this time I started a little earlier in the evening, which allowed the moonlight to provide more even illumination throughout the foreground. Conditions dictated an aperture of f/8 and a shutter speed of 5 minutes. That was clearly not long enough for star trails, so I needed to shoot multiple frames to stack in post-production. After setting up my composition, I calculated that to get an hour and a half of exposure time, I would need to shoot 18 5-minute exposures. I set my ShutterBoss II intervalometer and sat back to enjoy the night.

My reshoot solved all the problems, and I had an image I was happy with.

Take 2, March 2012. Nikon D700, Nikon 35mm f/2 lens. 18 5-minute exposures at f.8, ISO 200.

Newfound Gap, Great Smoky Mountains National Park

by Matt Hill

Visiting Great Smoky Mountains National Park two years in a row was a real treat. One of my favorite views includes a portal to see the road you drive to get up to Newfound Gap. So, car trails plus star trails!

On my first visit, I had a crazy mix of clouds, thunderstorms and Milky Way. Plus, the namesake smokiness the mountains exude was drifting over the peak into the scene. (I wrote about this photo last year—see “How I Got the Shot: Car and Star Trails in Great Smoky Mountains National Park.”) It was simply magical. But so much about executing the image involved compensating for obstacles to my vision. Which is fine—that’s part of photography—heck, it’s part of art (and life) in general. But I knew there was more potential in that place and in that idea.

Take 1, May 2018. Nikon D850 with a Nikon 70-200mm f/2.8 lens. 960 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 400.

This year, I was running a workshop in Great Smoky Mountains with Lance. We took the group (and Chris, who was visiting from nearby!) up to Newfound Gap, and all the obstacles from the year before were absent. The weather was entirely different. Clear. Crisply cold. Expectant. Awaiting the coming moonrise. So I set up to shoot it again. The result was a pastel mix of yellows and greens from the horizon to the star field, and then clear-as-a-bell star trails.

I was smitten. Both photos earned a place for months as the lock screen on my phone. And if I had to choose, I couldn’t say which was superior. I love them both. You?

Take 2, May 2019. Nikon Z6 and a Nikon 70-200mm f/2.8. 871 Seconds, f/4, ISO 200.

We all reshoot, right?

When have you revisited a location to improve upon an idea? We’d love to see your images and hear your stories!

Please share in the Comments section below or on our Facebook page.