Analyzing classic photographs can be an effective way to progress in one’s own work. The key is not to simply mimic someone else’s great ideas, but to use the knowledge that comes with reproducing the work of masters and move on to create something new. With this in mind, National Parks at Night's Lance Keimig offers this ongoing series highlighting some of the early masters of night photography. We'd love to see any photographs you create after learning more about the pioneers of this niche—please share in the comments section!

The great Hungarian photographer Brassai is arguably the most influential night photographer of all time, particularly due to his work during the 1930s after the release of his seminal book, Paris De Nuit. I was introduced to Brassai while studying with Steve Harper in San Francisco in the late 1980s, shortly after Paris De Nuit was reprinted in the classic Parthenon edition in 1987.

Last year I wrote about Howard Burdekin and John Morrison, who paid a backhanded compliment to Brassai in their own book London Night. The English photographer Bill Brandt admired and even copied Brassai’s night work. But this article is not about Brassai, but rather about Volkmar Kurt Wentzel, a German American photographer who also found inspiration in the pages of Brassai’s Parisian nocturnes.

“Lafayette Square.” A silhouetted sculpture of Andrew Jackson on a rearing horse opposite the North Portico of the White House. Wentzel used an exposure that kept the sculpture in shadow, but preserved the detail of the illuminated White House. As was typical of this series, Wentzel chose to photograph on a wet and foggy night, a strategy that he no doubt observed in the night work of Brassai, and perhaps in Stieglitz’s as well.

Wentzel moved to America in 1926 at the age of 9, when his father, an amateur photographer and photo chemical salesman from Dresden, Germany, was offered a job as director of an Ansco photographic paper manufacturing plant in New York. Wentzel’s mother died a few years later, after which he set off with a friend on foot for South America.

After three days of walking and hitch-hiking, they found themselves in Washington, D.C., where the two parted ways. The friend went home to his mother, and Wentzel rented a room in Lafayette Square near the White House. He found a job working in the darkroom of Underwood & Underwood portraiture studio and news agency, where he also assisted the staff photographers. His first break came when one of his images was published in a Washington newspaper.

“The Waterfront.” The Washington canal was where fishermen delivered and sold their catch from the Chesapeake Bay to the restaurants and wealthy homes of Washington, D.C. In this image, a fisherman shows his catch to a customer in the shadow of the Washington Monument.

“National Archives.” The National Archives building had just been completed in 1935 when Wentzel made this image on a foggy night. Two groups of people illustrate the grand scale of the building, and the looming presence of the bare trees in the foreground add an air of mystery to the image.

After being given a copy of Paris De Nuit by a friend, Wentzel began to photograph the well-known landmarks of D.C. at night. He often would process his images the same night, and then go out again to reshoot to improve his exposures, often staying out until dawn.

Wentzel’s next big break came in 1936 when a chance tour of the photographic facilities of National Geographic led him to discover that there was a job opening. He fortuitously had some of his night prints with him, and was granted an interview and then the job.

“U.S. Capitol.” Shot on a rainy night, the squares in the plaza reflect a darker side of the dome of the Capitol. There is a great irony in our majestic Capitol building–– the finial atop the dome is a nearly 20-foot statue of a woman titled “Freedom,” designed by sculptor Thomas Crawford, and cast in bronze by slave labor in 1863.

“The Mall.” The classic view of Washington: the Capitol peeking out from behind the Washington Monument as viewed from between the columns of the Lincoln Memorial. The shadowy figure in the foreground is Wentzel’s friend Eric Menke, the man who gave him his copy of Barassai’s book.

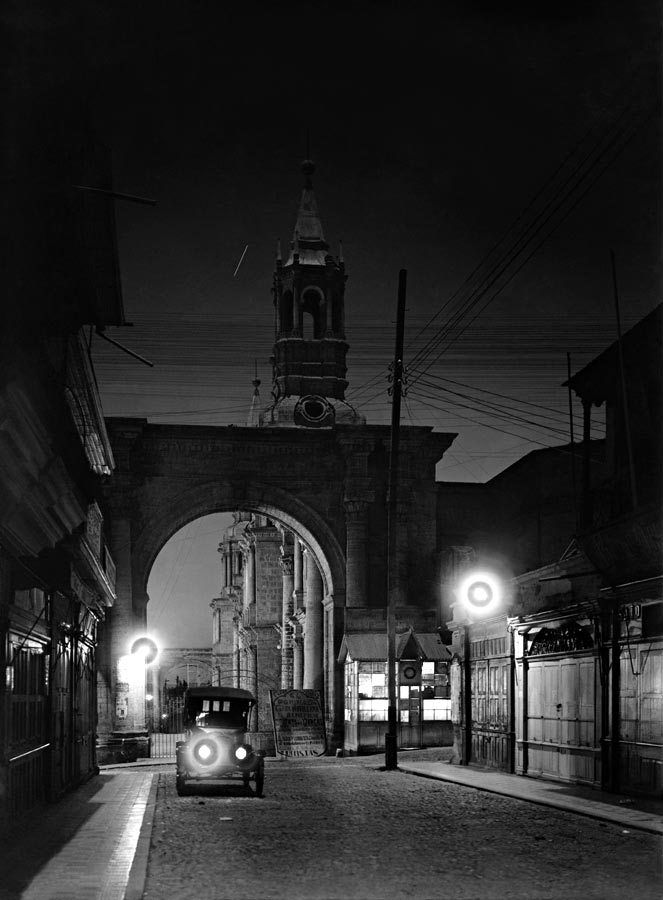

“Pennsylvania Avenue.” An image made on a snowy night from behind the gates of the Treasury building to the Capitol. Note the reflections off of the street car tracks, and the trails from car headlights, but not tail lights. Perhaps tail lights didn’t yet exist in the 1930s, or they were so dim as to not register on Wentzel’s film. The tower on the right is the old post office.

Although he was hired as a darkroom technician, in less than a year Wentzel had an opportunity to complete an assignment for the magazine when a photographer was pulled from a job in West Virginia for another story. Wentzel had spent time in West Virginia, and his familiarity landed him the assignment. It was the beginning of a career that spanned nearly 50 years at the magazine, where he photographed 45 stories and authored 10. He traveled extensively in Africa and Asia, and was later named the director of the National Geographic archives, where he was responsible for saving millions of images that had been destined for the rubbish bin.

Wentzel did not photograph extensively at night after his early Washington images, but they were shown at the Royal Photographic Society in England and at other venues in Europe before being published in the April 1940 issue of National Geographic. An exhibition of the work was presented by the Corcoran Gallery of Art, and published in book form as Washington By Night in 1992.

“Decatur House.” A shallow depth of field detail image of Decatur House at the corner of Jackson Place and H Street in Lafayette Square. The square had long been one of the most prestigious addresses in Washington, with the residences of presidents, vice presidents, secretaries of state, and other wealthy and powerful people. Wentzel planted the light bulb behind the frame of the lamp to minimize overexposure, but the light bled out from the sides all the same. You can just make out a row of late-1930s cars in the middle ground.

“National Archives II.” A dramatic image of the sculpture “Guardianship” by James Earle Fraser, best-known as the designer of the buffalo nickel. Fraser’s sculpture graces many of the buildings constructed during the New Deal era. Beneath the sculpture is a quote by Thomas Jefferson: “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.” Careful placement of a light source behind the sculpture adds to the drama.

Wentzel died in 2006 at age 92. Unfortunately, little is known about the technical aspects of his early night work, other than that he printed it at Underwood & Underwood studios, “surreptitiously using their best portrait paper” (as he writes in his book). He used a 4x5 Speed Graphic camera, occasionally supplementing the existing light with flashbulbs that, as he wrote, “were in fashion at the time.”